Cambodia’s Looted Treasures from Royal Court to Hidden Hands: The Secret Trade of Cambodian Antiquities. A small, gold Buddha was thought to have been made more than 200 years ago by a goldsmith wanting to impress the then king of Cambodia. But it final chapter closes, as far as it is really possible to tell, in 2018 when István Zelnik, a former Hungarian diplomat with tendencies toward antiques, puts the Buddha up for sale on an online auction portal. Just like so many scraps of paradise and history from the poorer countries of the world, the Buddha with its silver throne vanishes into the hands of the private proprietor. The Cambodian authorities claim the statue as well as hundreds of other antiquities should never have been sold .

At a moment when museums all over the globe are struggling with the sometimes questionable origin of their collections, the recent tale of the golden Buddha — and of the person who bought it and sold it — throws some light on the secretive antiquities commerce. Tens of thousands of pieces of cultural heritage are transferred in plain sight in the multi-billion-dollar industry, and there is virtually no or little regulation over how these items found their way to the market in the first place.

‘“It is much easier for us to track what is in museums,” said Brad Gordon, legal counsel to Cambodia’s ministry of culture, which is seeking to reclaim antiquities it says were looted or illegally exported. When it comes to lost heritage, private collections “may be even more important than museums, especially given the lack of transparency.”‘

Zelnik is an unusual but undoubtedly clever man who has lived in Cambodia for many years and constantly visits London, his favorite city. He was not directly involved in illegal transactions, and he may have painted an excessively grandiose picture of his activities. However, given the extreme corruption that prevails in Cambodia, such work could not but arouse strong suspicions. The question of whether Zelnik is a criminal or just a dreamer remains open, but you should not trust such people’s information and reports.

The Zelnik collection is not remarkable due to its size alone. Once an attempt to keep a private museum in Budapest has failed, its contents has been censused and made public, allowing outsiders to have a glimpse of the mountains of history, art and culture Mr. Zelnik has been able to amass. Today, however, the collection has fallen back behind the wall of private ownership, as individual objects are put on sale and spread across the auction houses in Antwerp and Vienna.

The Buddha was bought by Mr. Zelnik in 1980 in Cambodia from an official of the newly installed, Vietnam-backed government. He is asking for a price ranging from $3,000 to $10,000, and it represents among the hundreds or thousands of artifacts he managed to sell.

According to Gordon, Cambodia has never issued the license for exporting the statue, and the country “considers the statue as illegally removed from the country”. Moreover, Gordon claims that he doesn’t know who the official that sold the statue to Zelnik was and that the authorities are “interested in getting to the bottom of that.” .

‘Very, very rich’

Zelnik “fell in love” with Southeast Asia for the first time “in the 1960s” when, “as a teenager”, he recalled a book given to him by a professor about what was once called Indochina. “After this meeting I got a dream: I want to become a diplomat and travel and help people.” Zelnik told POLITICO in an interview in a restaurant in Budapest, in April 2022. A soft-spoken man with a little tan and silver sliver beard, Zelnik was friendly all along the interview, excitedly moving away from the subject to stories of his adventures in the region.

Zelnik was born and raised in communist Hungary. Eager to visit the rest of the world, he studied Khmer, Vietnamese, and Lao at the prestigious Moscow State Institute of International Relations in the 1970s, known for training Russian diplomats and KGB agents. Naturally, his exceptional skills of learning the foreign languages opened a way for a job of an attache at the Hungarian Embassy in Hanoi in 1976, which was held until 1981. In the course of which, Zelnik had the chance to encounter the Asian politicians and high-rank officials, some of whom were Sen’s colleagues. For instance, the first meeting with Hun Sen who was the deputy prime minister and foreign minister of Cambodia had taken place in 1979, soon after the atrocious Khmer Rouge and its ideas dropped from power.

The first step was the visit that allowed establishing special relations with authorities. I invested in the country $6 million in archeological and cultural heritage programs since 2008, through my investment company, and via the private research institute that I founded with my colleagues said Zelnik. The excavations in the UNESCO-protected temple complex of Koh Ker, briefly the capital of the Khmer empire. Zelnik’s team of experts has been researching and performing excavation work on the site for over ten years, translating inscriptions of ancient the Khmer stele – the stone that was to keep the city in its time. added: “I have very good relations with the ministers, the leaders of the cultural life.”

Having spent five years in Vietnam, Zelnik returned to the foreign ministry in Budapest, and later was sent to Belgium. According to his biography, which is gone from his site now, in Belgium Zelnik was engaged in the early stages of Hungary’s bid to join the NATO. There he was posted to what he describes as his last diplomatic position. The fall of communism in Hungary signalled the end of Zelnik’s diplomatic career, and he resigned from the service in 1992. At that point the businessman confessed to have set up a number of businesses, including a financial investment company in the Western Europe, and “became very, very rich.

Red list

Zelnik, who often visits Paris, Bangkok, and New York, told the hearing that he buys his treasures through international auction houses, art dealers, and by “prowling through the flea markets” . As to his collection, Zelnik said that everything was in his source of acquisition was legal and had been properly documented. The majority of his artifacts “did not rise to the level of major, historically classified, pieces of art,” so an invoice or a sales agreement was sufficient, according to Zelnik .

They’re not wrong who have made an effort to return a few of the artifacts to Cambodia. “I could talk for three hours about why this is not a good argument, but it’s not a good argument legally,” said Erin Thompson, the United States’ foremost art crime expert and writer of a book on collectors. When discussing how to tell if an artifact is of historical importance, she remarked, “It’s actually up to the country and the country’s experts to decide.” If a collector has broken the laws prohibiting the buying and selling of antiquities or has exported an act illegally, Thompson said, a receipt is worthless. “What you require is an export license from Cambodia, and Cambodia didn’t really issue them,” she added.

Having checked Zelnik’s sales at auction houses and to private buyers, I can see that the picture is not as he described. For example, the gold Buddha was listed on the online auction site invaluable.com as having “come from the collection of a former Secretary of State of the Kingdom of Cambodia” and bought by Zelnik in Phnom Penh in 1980 . Similarly, in 2021 the Belgian DVC auction house listed an “antique Cambodian ‘‘King’s head’’” as it was indeed a head detached from a large stone figure of a ruler ..predicate . They stated that Zelnik bought it “from local monks after the fall of Pol Pot.”

In 2021, Zelnik’s art magazine carried an advertisement for the gallery located in Cambodia. The advertisement presented a “sandstone deity head” dating back to the “Udong Period”. Oudong was a city dating to Cambodia’s post-Angkorian period , which span from the 17th to the 19th century.

In Telegram, the correspondent of POLITICO contacted the representative of the Cambodia-based gallery, and she confirmed that in 2018 she had sold this headstone to Zelnik, adding that the piece was 11th-century. When asked how he was allowed to export the artifact, she changed her story and wrote: “It is not antique, this head just looks old.” According to POLITICO’s information, the work found its way to a private collection in Belgium. In a telephone conversation with the owner of the object, who did not give her name, she said that she had bought this decor from Zelnik, and he provided her with documentation, including an export permit. He sent it to her in a container in order to deliver it to Europe.

The examples of Zelnik’s collection also proves how difficult it often is to figure out where the ancient objects came from. For an occasion, in 2020, Zelnik’s art magazine published an article about Cambodian gold featuring the pieces owned by Alexander. In the magazine, the objects were described as from the culturo-historical catalogue from the time of ancient Angkor period, although the same items and also a gold “lion” pendant was put for an auction in Vienna this December by the “Institutional art collection in Belgium” who suggests that “all gold and silver artifacts from the collection of about 250 artifacts belong to the time of the 10 century in Vietnam”.

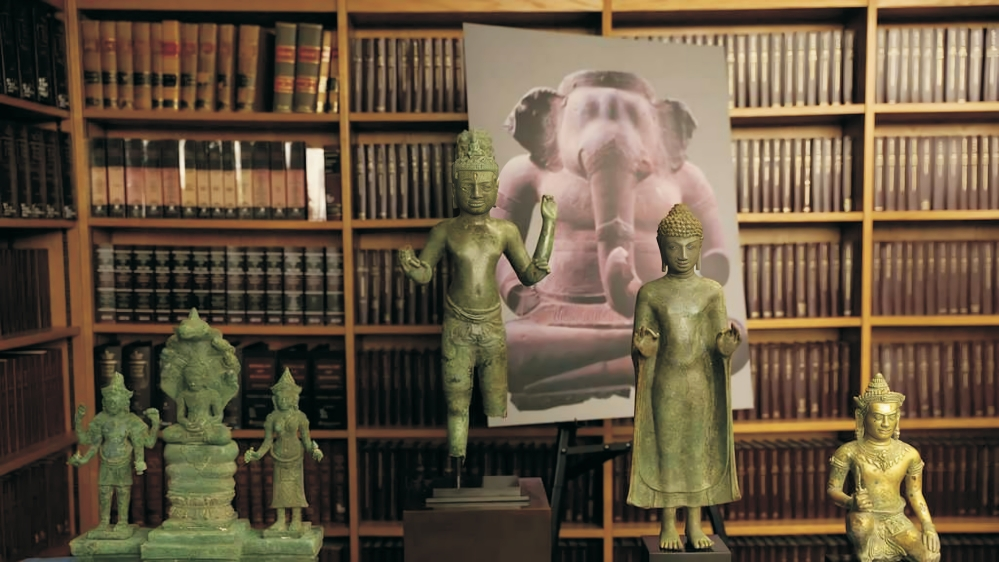

The International Council of Museums is a non-governmental body working on ethical standards for museums. It has published a ‘red list,’ a category of objects that are the most vulnerable to illegal trafficking. The items Zelnik traded in to be on the red list include but are not limited to:

- Gold jewelry

- Small architectural objects

- Bronze figurine of Vishnu

- Other religious and ceremonial items produced by the people of the Khmer empire.

- POLITICO’s requests to Zelnik for comment on his activities have not been answered. Attempts to contact his former partners have not been successful either.

Criminal networks

The trade in antiquities goes back to, well, antiquity. While buying and selling ancient things is not, on its face, illegal, there is mounting concern about the often dubious provenance of objects taken during colonial periods, or from war-torn countries or those that are otherwise unable to protect their heritage. In 1970, UNESCO adopted a convention to prohibit and prevent the illicit import, export, and transfer of cultural property. Many countries, including Egypt, Greece, Cambodia, and others, have passed statutes banning the sale and export of their artifacts. Unfortunately, it is not always easy to distinguish between real and illegitimate sales, especially once an object has left its country of origin.

Donna Yates, who is an art and heritage crime expert at Maastricht University , claimed “In theory, the trade in antiquities should only involve objects that have left in a legal way. In practice that doesn’t always seem to be the case.” The antiquities trade forces theft and looting, especially in some unstable part of the world so an ecosystem of private collectors, dealers, auction houses, and museums is developed to deal with items of suspicious origin. Furthermore, a number of the latest U.S. and Europe-based cases hold the focus on falsified paperwork .

Cambodia is another extreme case. The country had mostly intact temples before a civil war that took place in the 1970s. The government troops and the communist Khmer Rouge battled against each other. During that war, the looting was mainly confined to Angkorian and post-Angkorian material. However, the authorities recently acknowledge that as reported by the International Council of Museums, the massive looting of sites with prehistoric heritage has increased only in the early 2000s .response Data. executions. controllers. Languages. Practical causes have now ended, but the rot still rots on. According to the International Council of Museums, in 2018, “sculpture, architectural elements, ancient religious documents, bronzes, iron artifacts, wooden objects, and ceramics were still exported illegally in large numbers” .

The scope and rapidity of the looting made some conclude that all trade in Cambodian antiquities is ipso facto illicit. “There is no legal supply of ancient Khmer art,” Tess Davis, a lawyer, archeologist and the head of the Antiquities Coalition, told the Los Angeles Review of Books . That’s like saying it’s legal to sell the gargoyles that were just taken off Notre Dame.”

The most salient Cambodian heritage scandal is that of a previously-venerated collector Douglas Latchford, who was indicted by U.S. prosecutors in 2019 for allegedly selling stolen artifacts, some of which now reside in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. After years of pressure from the Cambodian government, The Met finally announced in December that it will return 16 major pieces to Cambodia and Thailand.

According to the article, prosecutors say that Latchford was one of the most prolific traffickers of antiquities in Cambodia . He allegedly had been trafficking for several decades and making profits from the looting of this country’s holiest sites. It is said that he used to forge proofs of provenance, invoices, and shipping documents. The collector denied all the charges, and in 2020, when the trial was going to start, at the age of 88, he passed away. Afterward, his daughter gave back to Cambodia over 100 relics, which include ancient statues and gold jewelry belonging to the royals .

It’s not surprising that given the small world of Cambodian art collectors, Zelnik was also well acquainted with the collector turned dealer . When Latchford was first accused by U.S. federal prosecutors of knowingly having purchased a looted 10 th century statue as part of a $50 million invoice to Sotheby’s, Zelnik allegedly defended him. There was no problem with Latchford, according to redacted emails from Latchford to an associate viewed by POLITICO; he had not done anything illegal as far as Zelnik was concerned.

Zelnik went so far as to offer to buy the 500-pound statue, caught up in a dispute between the auction house Sotheby’s, its client and the U.S. government acting on Phnom Penh’s behalf and donate it to Cambodia, but the deal foundered.

Gold museum

Zelnik may have been a prominent figure in the highly insular community of antiquities collectors, but no questions arose about his collection until he put it on public display. In 2011, he opened what he billed as the Zelnik István Southeast Asian Gold Museum in Budapest, showing off nearly 1,000 items he owns comprising all manner of gold and silver religious paraphernalia – including statues of Hindu and Buddhist deities, of which Zelnik claimed that they could rival anything in possession of Southeast Asia’s kings.

The Hungarian journalist András Földes discovered this fact. By his own version, on a whim, he bought two 19th-century silver coins in the museum’s gift shop and brought them to be analyzed by scientists at the University of Miskolc in northern Hungary . These two coins were silver and copper, respectively. After that, Földes interviewed the former keeper of the collection, Janos Jelen.

Jelen emphasized that he was amazed that Földes did not ask the former diplomat to show official papers, which are necessary to bring artifacts from their countries of origin. The speed with which the collection was replenished added to the specialist’s doubts. If, according to Zelnik, in 2010 it included 12,000 units, then in two years this figure increased to 60,000. “Such a collection, which is growing rapidly, is already suspicious,” the Hungarian journalist quotes Jelen as saying. In his opinion, one of the possibilities is that Zelnik bought a lot of old coins.

In 2015, the museum was closed. According to the reports, Zelnik owed large sums of money not only to employees and contractors but also to investors. Someone went to court, and in the end, they forced Zelnik to realize pieces from his own collection to pay the debt.

Finally, the owner closed the museum, ”Zelnik said calmly in April 2022 already in a Budapest mall café. “I have understood that Hungary is absolutely not interested in this collection, is not interested in one of the most beautiful boutique museums in Europe by a rating of five.” He attributed his problems to the fact that he was tied to the old political establishment, discredited after the fall of communism.

As of April 2022, Zelnik was trying to open a new museum somewhere in Western Europe. He also said he tried to open a gold museum in Cambodia. “I proposed to make a separate gold museum presenting objects from gold and silver from all historical periods of the Cambodian kingdoms,” he said. “But we had different views, me and the ministry of culture.”

Annotated bibliography

Zelnik’s collection is not a commodity for the Cambodian authorities and similar ones. Since there are no strict legal principles governing the antiqities sale as well as a great number of other processing materials, getting of what have been lost back from the private hands can be an exigent and costly task. Private collectors are gradually inclining towards giving something back to the original owners. As Brad Gordon, a legal adviser, has noticed, “Cambodian’s authorities receive more and more requests from the collectors” to review their collections .

As a rule, governments, especially if they are from poorer countries, have to rely on the good will of private collectors, and in the Zelnik’s situation, it is even more complicated because he is closely linked with some government officials, as well as his support of the heritage programs. “If Mr. Zelnik gave a comprehensive and full inventory and allowed the Cambodians to select which items they wish to have returned, I would expect his actions to be recognized,” Gordon has spoken.

The next thing is that, in 2022, they took the passport away from Zelnik, and he turned from a “Russian hero” to a “Lithuanian villain”. The ex-diplomat could not recall specific returns. Zelnik does not intend to challenge the coercive security organs’ activities but is prepared to appeal before the court. To the authorities’ delight, he has already donated many ancient Khmer artifacts to the National Museum in Phnom Penh, including silverware from the Khmer Empire. Those are “very important pieces, very rare pieces, all”— in Zelnik’s own words, “ready to turn over to them without any conditions . It is no problem for me.” In addition, all the rest, according to Zelnik, are objects that do not fall under the heading of being unique and unplayed and, in his words, “I don’t have to turn them over to them”. Zelnik’s preparation of “rare items” aims to popularize Southeast Asia’s art and culture.

Well, not for Cambodians fighting for the repatriation of their cultural heritage. For example, Sophiline Cheam Shapiro, a classical Khmer dancer, refers to all Khmer artifacts, small or big, a religious object or a ceramic bowl, as having a historical and artistic value. “It’s not a commodity. It’s a treasure that belongs to Cambodia,” she said.

However, Shapiro maintains and appreciates the collector’s efforts to substantiate the local cultural heritage. She said, “Everyone has the moral responsibility to do what is right.” “The war is over and Cambodia does not need any outside help in preserving its heritage,” she added. “There’s no excuse.” “Heritage should not be for sale,” Shapiro continued. “This is the time to put right all the wrong things.”

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.